Editorials

Why The Scariest Movie Ever Made Isn’t A Horror Movie: Come and See

Elem Klimov’s 1985 film Come and See starts out not unlike many other war films, with a scene conceptualizing the day-to-day life in a war zone. Taking place in Belorussia in 1943, we are offered a glimpse of the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union through two children, who are eager to find an abandoned gun in order to enlist in the partisan resistance fighters.

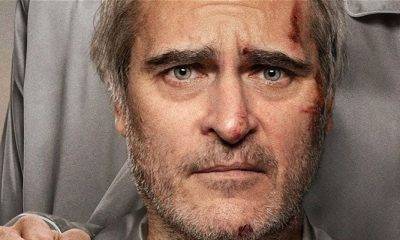

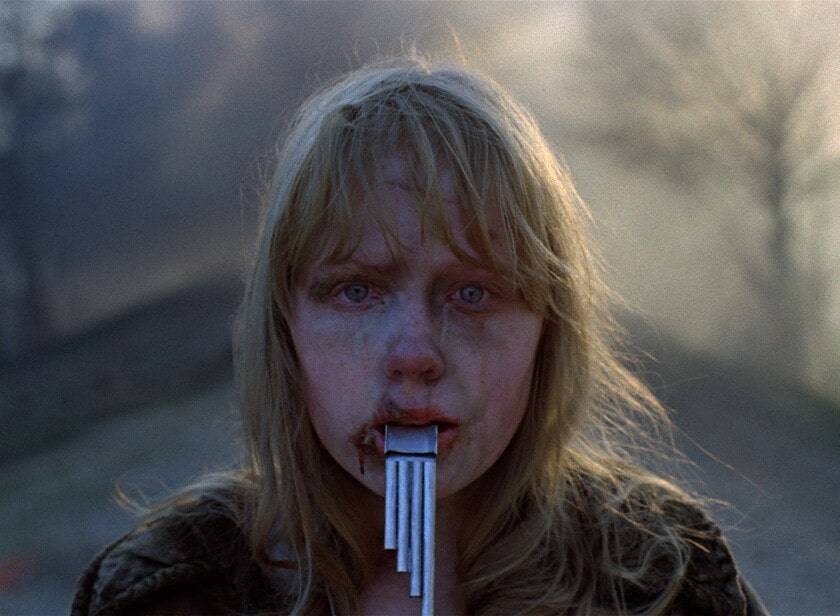

We follow a young teenager Fliora, who is eager to get involved and prove how brave and strong he is. Indeed, Fliora is all smiles when even getting chastised and punished by his commanding officer. He embodies the hope of freedom fighters who strive to protect their people and win the day. Unfortunately, Fliora doesn’t understand the dangers he’s getting himself into, and what follows is a brutal struggle for survival and a living testimony to the travesty afflicted on the people of the Soviet Union at the hands of Nazi officers, officials, and collaborators.

Much of the horror of Come and See comes from how the film was produced, which follows many horror conventions. Instead of focusing on large scale battles or the commanders of armies, we follow the experience of a teenage resistance fighter who barely knows how to operate a rifle at the beginning of the film. Fliora is a powerless protagonist, much like the characters in horror films who are powerless against a ruthless killer or supernatural entity.

Likewise, the scenery and landscape begins to change with Fliora, beginning with natural colors and greenery but quickly becomes grey and overcast, almost polluted. Like war is this all-encompassing entity that corrupts everything it touches. Even tempered moments of calm are inter-cut with disturbing music and sound effects that leave the viewer with an uncomfortable, uncanny feeling. Something is not right here, and we’re right to assume so.

The real horror behind Come and See is in its ability to draw from realism. The film’s screenplay was inspired by the 1943 Khatyn Massacre, in which a Nazi SS battalion massacred almost the entire population of the village in retaliation for an attack by Soviet partisans on German troops. Indeed, co-writer Ales Adamovich fought as a part of a resistance group in Belarus when it fell under Nazi occupation, leading to the film’s gritty and brutal realism. Many may not realize that by the time the first death camps were finished being constructed, the Holocaust was already well underway in territories east of Germany, costing the lives of an estimated 2-4 million people over the course of three years. This involved the extermination of entire villages and populations in mass killings through shootings and the burning of entire towns along with their inhabitants.

This is depicted in Come and See in what must be the most gruesome and visceral scene in cinema history, where we see an entire town’s population being burned alive inside an old church. The Nazis officiating this travesty at first permit them to escape if they leave their children inside, which of course none of them do, labeling the Nazis (appropriately) as “beasts.” The Germans are portrayed as sadistic, outright malicious for no reason other than control and “purification.” Once their evil deeds have been accomplished they leave, with nothing more to gain than pure and utter destruction. Fliora, our poor protagonist, is left a living witness to this tragedy, all at once a depiction of the utter desolation and hopelessness felt by the victims of war, undoubtedly envying the dead.

Make no mistake, Come and See is extremely difficult to watch, and that is by design. Director Elem Klimov intended to make a film that made a difference, and oftentimes in that pursuit we must face ugly, terrible realities. Ending the film on real footage of Holocaust victims truly drives home one of the prevailing themes of the film, which explores the extent of the human endeavor to cause suffering to others. In one of the last, and perhaps the most powerful scenes of the film, Fliora comes upon a fallen portrait of Adolf Hitler. In what might be the only time we see him use his gun, Fliora shoots the face of Hitler over and over, while a powerful montage plays, going through the real history of the war and Hitler’s life. Much like all victims of war, Fliora wishes he could turn it all back, that it never happened and never came to his home. Wishes that he, or someone, anyone, could kill Hitler and reverse all of this. But even then, when the montage crescendos to an image of baby Hitler, even Fliora realizes that killing a baby would make him no better than the Nazis. Despite everything, there’s nothing he, or anyone, can do to stop this.

This is what we are left with by the end of the film. This is only a small glimpse of what the Nazis truly did inflict upon innocent people, and even by the films end there would still be two more years of suffering to come. And still, we see Fliora run off to join the resistance fighting once again. Despite the utter horrors and trauma he has gone through, and despite knowing that they would have very little success, there is still hope to be found. Perhaps it is all futile and perhaps we are seeing these young men march off to their deaths, but it instills in us the capacity for the human spirit to rise and fight against such evil.